The question of whether can a river be private property is a puzzle that has perplexed boaters, anglers, and landowners for generations, sparking countless dockside debates. It’s a topic that dives deep into the heart of land ownership, public access, and the very nature of our waterways. The answer isn’t a simple yes or no; it’s a fascinating tapestry woven from centuries of legal precedent, defined by concepts like riparian rights, the critical distinction between navigable waters, and the foundational public trust doctrine. Understanding these principles is not just academic—it’s essential for anyone who loves to be on or near the water, ensuring your weekend paddle doesn’t turn into an unexpected lesson in trespassing law.

The Core of the Matter: Navigable vs. Non-Navigable Waters

At the heart of river ownership lies a crucial legal distinction: is the river considered “navigable” or “non-navigable”? This single factor often determines who controls the riverbed and who has the right to use the water’s surface. Think of it as the river’s legal status.

Navigable waters are generally defined as rivers that are, or have been, used for commercial transport, such as floating logs or moving goods on barges. Under federal law and the laws of most states, the beds of navigable rivers are owned by the state and held in trust for the public. This means that even if your property line runs right to the river’s edge, the state owns the land beneath the water up to the ordinary high-water mark. Consequently, the public has a right to use the surface of these waters for recreation, including boating, fishing, and swimming. You can’t put a chain across a navigable river and declare it your own.

On the other hand, non-navigable streams are typically smaller waterways that cannot support commercial traffic. In these cases, the ownership rules can change dramatically. Landowners whose property abuts a non-navigable stream often own the riverbed to the center of the waterway. If a single person owns the land on both sides, they may own the entire stretch of the riverbed as it passes through their property. This grants them far more control, but as we’ll see, it still doesn’t usually mean they own the water itself.

Understanding Riparian Rights: What Do Landowners Actually Own?

The term you’ll hear thrown around most often in these discussions is “riparian rights.” This refers to the system of rights held by a person who owns land adjacent to a river or stream. It’s a bundle of entitlements that includes the right to use the water for domestic purposes, build a dock, and access the water from their property. However, it’s also a bundle of limitations.

Ownership to the High-Water Mark

For most navigable rivers, a landowner’s property ends at the “ordinary high-water mark.” This is the visible line on the bank where the presence and action of the water are so continuous as to leave a distinct mark, either by erosion, destruction of terrestrial vegetation, or other recognizable signs. The land below this mark, the riverbed and the foreshore, belongs to the public. This is why you can often walk along the wet sand or gravel of a riverbank without trespassing, as long as you stay below that line. It creates a public corridor, a foundational concept for recreational access.

The Myth of Owning the Water Itself

Here’s a critical point that often gets lost: even if you own the riverbed of a non-navigable stream, you do not own the flowing water. The water is considered a public resource, a “corpus” that is always in motion and belongs to the people of the state. Your riparian rights grant you the right to use the water reasonably, but you cannot stop its flow, divert it entirely for your own purposes to the detriment of downstream neighbors, or pollute it. It’s a right of usufruct—the right to use and enjoy the property of another without destroying it.

Expert Insight from Dr. Alistair Finch, Maritime Law Specialist:

“People often confuse owning the land under a river with owning the river itself. The Public Trust Doctrine is a powerful, centuries-old legal concept asserting that vital natural resources like major waterways are held in trust by the government for the benefit of all citizens. This principle ensures that private ownership doesn’t choke off public access and recreation.”

The Public Trust Doctrine: A Cornerstone of Water Access

The Public Trust Doctrine is the legal bedrock that preserves public access to many waterways. It’s an idea inherited from English common law, which itself drew from ancient Roman law. The doctrine essentially states that sovereign governments hold submerged lands and waters in trust for the public’s use in navigation, commerce, and fishing. Over time, courts have expanded this to include recreational activities like swimming, boating, and kayaking.

This doctrine is the reason why, even when a river flows entirely through private lands, the public often retains the right to float on its surface. It acts as a powerful check on the concept of absolute private property when it comes to shared natural resources. It affirms that some things are too important to be exclusively privatized, and the free flow of a river is one of them.

So, Can You Trespass on a River?

This is the ultimate practical question for any boater or kayaker. The answer, frustratingly, is: it depends. On a clearly navigable river, it is nearly impossible to be charged with trespassing as long as you are on the water or below the high-water mark. You are exercising your right as a member of the public.

The gray area emerges on smaller, non-navigable streams that flow through private property. While the landowner may own the streambed, many states still grant the public an “easement” or right to use the water for passage. This is where things get tricky and can vary wildly from one state to another.

The ‘One-Foot-in-the-Water’ Rule

A common rule of thumb for recreational users is the “one-foot-in-the-water” principle. It suggests that as long as you are physically in the river—wading, floating, or boating—you are generally not trespassing on the adjacent private land. The moment you step out onto the dry bank above the high-water mark, you could be trespassing. This is why you should always be cautious about where you stop for a picnic or set up camp along a river.

Portaging and Obstructions

What if you encounter an obstruction like a fallen tree, a fence illegally strung across the water, or a small dam? The right to “portage”—getting out of the water to carry your vessel around an obstruction—is another legally complex area. In some states with strong public access laws, you have a right to portage around an obstruction in the most direct and least intrusive way possible. In others, stepping onto the bank for any reason is considered trespassing. This highlights the absolute necessity of knowing local regulations before you set out.

How State Laws Differ on River Property

It cannot be stressed enough: the answer to can a river be private property is intensely local. Federal law sets a baseline for navigable waters, but states have significant power to define navigability and public access rights for their own waterways. This has created a patchwork of laws across the country.

| Legal Approach | Description | Common in States Like… | Implications for Boaters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strict Title States | Ownership of the riverbed is paramount. If a river is non-navigable, the landowner owns the bed and can often restrict or prohibit public passage. | Virginia, Michigan | Extremely high risk of trespassing on smaller streams. Stick to designated public waterways. |

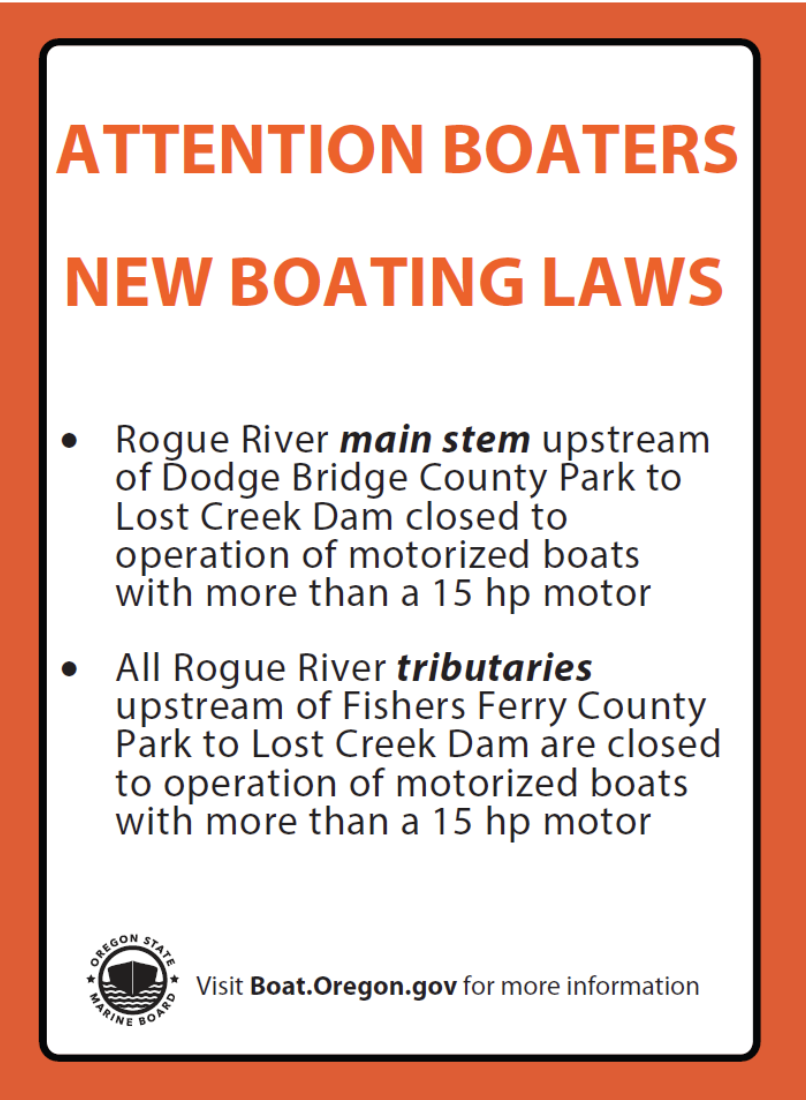

| Navigable-in-Fact States | If a river is capable of floating a canoe or kayak, it is considered open to public passage, regardless of who owns the bed. | Montana, Oregon | Much broader public access rights. Recreational use is generally permitted on most flowing waters. |

| Hybrid Approach | Laws blend elements of both, often relying on historical use or specific court rulings to define access on a river-by-river basis. | Texas, Colorado | Requires research into the specific river you plan to visit. Access rights can be inconsistent. |

Expert Insight from Dr. Alistair Finch, Maritime Law Specialist:

“Never assume the rules from one state apply in another. I’ve seen countless friendly float trips turn into legal disputes because someone crossed a state line and wasn’t aware the definition of public access had completely changed. A five-minute search of the state’s Department of Natural Resources website can save you a world of trouble.”

Practical Tips for Boaters and Watersport Enthusiasts

Navigating these murky legal waters doesn’t have to be intimidating. The key is to be prepared and respectful. Before heading out on a new river, always research the local and state regulations. A quick search for “[State Name] stream access laws” is a great starting point.

Always favor designated public access points, such as boat ramps at parks or bridges, for putting in and taking out your vessel. These are clear indicators that public access is permitted. If you’re floating through an area with “No Trespassing” signs posted along the banks, take them seriously. While the signs may not legally apply to you on the water, they are a clear signal that the landowner is sensitive to public presence. In these situations, stay in your boat, keep noise to a minimum, and do not get out on the banks. The goal is to be a good steward of the water and a respectful neighbor, ensuring these access rights remain for future generations.

The complex question of whether can a river be private property ultimately reveals a beautiful tension in our legal system—the balance between private ownership and the shared heritage of our natural resources. While you can own the land a river flows over, the water itself remains a public good, a powerful symbol of something that connects us all. By understanding the rules and respecting both private rights and public traditions, we can all continue to enjoy the rivers that carve their way through our landscapes and our lives.

Comments

Eleanor Vance

★★★★★ (5/5)

This is the most comprehensive and clear explanation I’ve ever read on this topic. I’m a kayaker in Oregon, and we’re lucky to have such great access laws. This article really helped me understand why those laws exist with the Public Trust Doctrine. Fantastic resource for anyone who uses our rivers!

Samuel McGregor

★★★★☆ (4/5)

As a landowner with a stream running through my property in Virginia, this article is very balanced. It correctly points out the difference between owning the streambed and owning the water. My main issue is with people leaving trash and not respecting the land. As long as floaters are respectful and stay in the water, I don’t have a problem. This piece does a good job of encouraging that respect.

Brianna Castillo

★★★★★ (5/5)

Thank you! My family and I were planning a canoe trip down a river that winds through a lot of farmland, and I was so worried about trespassing. The “one-foot-in-the-water” rule and the advice to check state laws were super practical. We looked up our state’s DNR page and now feel much more confident.

Declan Hayes

★★★☆☆ (3/5)

The information is good, but it just shows how confusing the laws are. A few years ago, I had a landowner yell at me for fishing from my kayak on what I thought was a public stream. We didn’t get into a legal fight, but it ruined the day. It would be nice if there was a single, national rule for this.

Isabelle Chen

★★★★★ (5/5)

The table comparing the different state approaches was brilliant. It instantly clarified why my experience boating in Montana felt so different from when I visited family back east. It’s a complex topic, but this article breaks it down perfectly for the average person. Sharing this with my paddleboarding group.